Vestige piece

2024

3:07 mins

digital

In the source video, I’m three years old. I don’t remember this moment, but there I am, preserved by my dad’s point-and-shoot camera. I’m in the living room of my childhood home; it must have been shortly after we moved in. My dad asks what I’m doing and I tell him I’m “dancin’,” and I press my small face up close to the camera lens. In another video, I spin around and around in circles, staring at my bare feet with an acute concentration, at times losing my balance and wobbling a bit in my irregular orbit.

Vestige piece is, for one, a meditation on the boundaries of my body. At that young age I was still unsure about my edges and limitations; each step was a conscious effort. I danced and spun in an attempt to understand my body in context. In some ways, I’m still trying to identify where my body ends and my environment begins. It’s a daily endeavor, informed by my interactions and relationships with other bodies, with landscapes, with what I consume and produce, with sensory entanglements. In What Gets Inside: Violent Entanglements and Toxic Boundaries in Mexico City, Anthropologist Dr. Elizabeth F. S. Roberts posits that “distinction between self and other lies not on the surface of bodies but deep inside, in the energy reserve, or the pool that is not quite the organism or the environment but the moving zone in which the ‘two become one’ (597). I do not think my body ends at the skin; it seems to me that it is permeable and only exists in its relations.

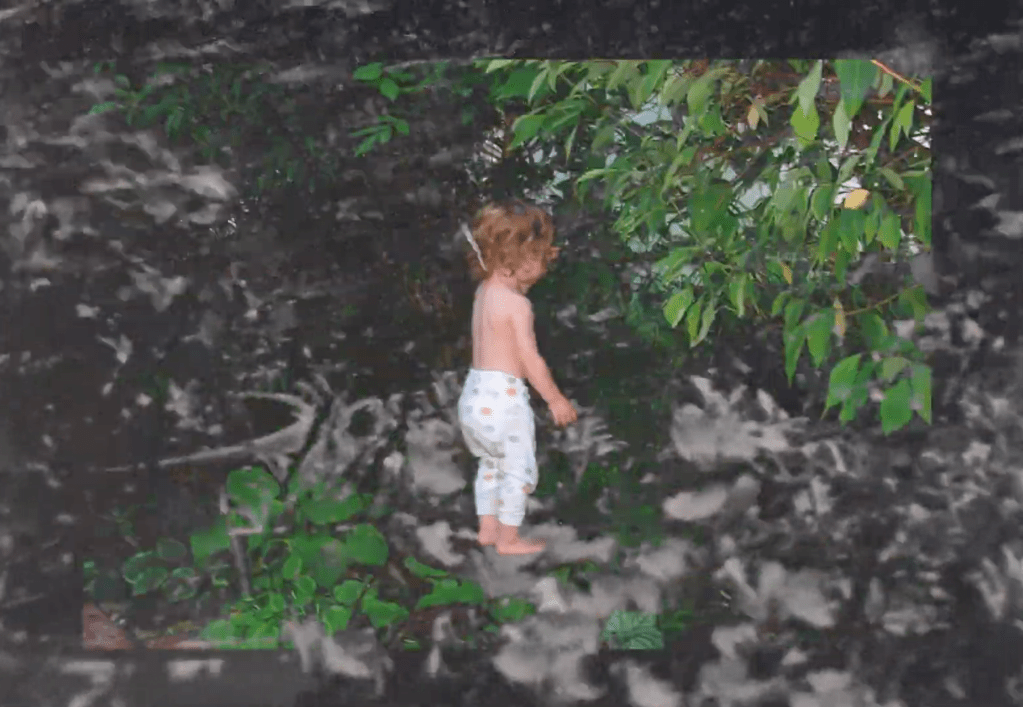

Besides the dancing videos, Vestige piece contains photographs of myself at age two exploring a garden. At that earlier time, my family lived in Minneapolis in a house we called “Daisy.” My mom attentively tended to its explosive garden and to me. In one picture, I stand opposite a plant that’s taller than I am, caressing its leaves with my tender hand. I have no memory of that time. Even the living room of my second house is hardly recognizable. Since then, walls have been torn down, furniture rearranged and replaced. And, though I can identify the child as myself, I barely resemble them. Roberts discusses a framework around permeability and persistence — what passes through the body and what continues inside of it. “Permeability,” she writes, “is the state or quality of a material or membrane that causes it to allow liquids or gases to pass through,” whereas persistence is the “firm or obstinate continuance in a course of action in spite of difficulty or opposition . . . the continued or prolonged existence of something” (597). In the years since those shots were captured, all of the cells in my body have been continuously replaced. But that’s still me — clearly I must be something beyond just a collection of cells. Despite the total upheaval of my body (or perhaps because of it), there is still some self that has persisted. A living Ship of Theseus, I exist outside of terms that are purely scientific.

Vestige piece also contains analog 16mm footage I shot last summer in Schimatari, Greece, where my Yia-Yia was raised. She immigrated to the United States to pursue a college education and never left. She gave birth to my two uncles and then, years later, to my dad. I was a baby when she passed. My uncles are near fluent in Greek and visit Schimatari often, but my dad doesn’t speak his mother’s language and hasn’t visited since he was young. Last summer was my first time there. In my Yia-Yia’s childhood home, where I stayed, there’s a faded photo of my dad and his brothers on the mantelpiece. Although he doesn’t hold many memories of that house, he does recall the huge mulberry tree in the backyard. And although I’d never been to Schimitari before, my body has ties to it. I ate mulberries from the same tree that generations of my family ate fruit from, and they tasted familiar.

In some sections of Vestige piece, the images of my young body are overlaid with abstract shapes of leaves and flowers, which flicker over the frame in a wash of warm oranges and pinks and browns. I made these plant images using a technique called Phytography, developed by artist-filmmaker Karel Doing in 2016. Phytography allows for the interaction of plants’ internal chemistry with photographic emulsion, resulting in kaleidoscopic and spontaneous images that seem to grow on the film strip. Foraged plants are soaked in a solution of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and sodium carbonate (washing soda), then laid on the film strip and allowed to sit under sunlight. The film is then dunked in a fixer solution to stop the chemical reaction. Images produced in this way highlight the indexical relationship between the photographic image and its object. The phytogram, along with every other form of photographic image, is more than an artistic rendering or approximation of a thing; it bears a scientific, material connection with the thing itself. As renowned film theorist and critic André Bazin writes in The Ontology of the Photographic Image: “No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, no matter how lacking, in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model” (8). This is the advantage of photography to other forms of storytelling: It is, in some objective, scientific way, a true representation of reality, and solicits a certain level of trust. Motion picture film, then, adds a temporal dimension to these true images. Even though I have no memory of the occasions in Vestige piece, I know they must be true, and in replaying the images I see some vestige of the event itself unfold again before my eyes.

The footage shot in Greece was also developed using plants, through a slightly different process. I boiled foraged plant matter until the fluids were extremely concentrated, and raised the solution’s pH with sodium carbonate, then added ascorbic acid. I used this solution in near total darkness to develop the images. Although the general recipe for eco-developing can follow similar steps, the results can be unpredictable, and are contingent on a multitude of relationships between the practitioner, their surrounding natural environment, the temperature and basicity of the developer, and so on. Researcher Dr. Max Liboiron discusses place-based sciences in their book “Pollution Is Colonialism” and points to a movement in sciences against universalism, or the idea that “science is independent of the place where it is practiced” (146). The protocol in Liboiron’s lab is place-specific, and might not be transferable to other contexts. Plant processing, too, is entirely place-specific, and even then can vary greatly depending on countless factors — seasons, parts of the plant, basicity and temperature of the developer, and so on. It is inseparable from its physical context.

Eco-processing also invites me to consider how I position my body in relation to film chemistry and analog development. Some plant processing practitioners, such as Katherine Bauer at L’Atelier MTK, reject ubiquitous scientific metrics and instead use their bodies to take measurements: The amount of plant matter needed for a developer recipe might be quantified in handfuls rather than kilograms. When I processed this footage, I followed suit. My notes describe the temperature of the plant solution as “warm like a cup of tea that I almost forgot about but remembered to drink before it got too cold.” This is a measurement that is true for me but might read differently for someone else. My hope is that this approach invites others to consider how they position their own bodies — boundaries, permeability, histories — and perhaps test out eco-filmmaking methods for themselves, and revise as they see fit.